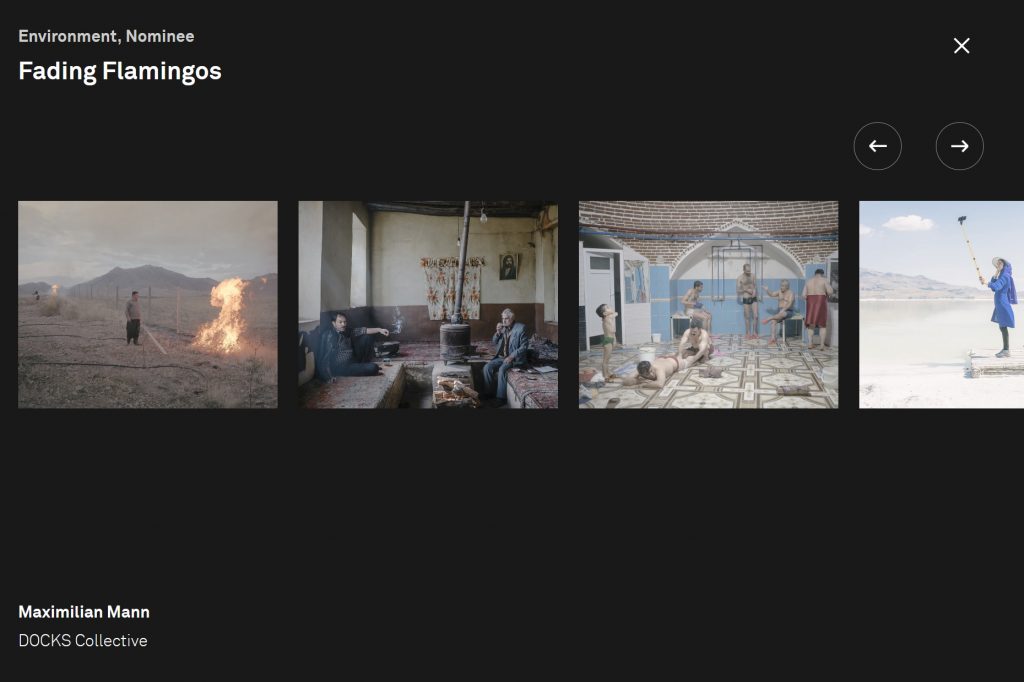

There was something uncannily familiar about a series among the recently announced nominees of the 2020 World Press Photo foundation’s annual industry flagship photo contest. Nominated in the environment category, “Fading Flamingos” of the German photographer Maximilian Mann is a set of carefully framed images with a brilliant aesthetic quality and a pastel hue addressing the issue of Lake Urmia. Browsing through it, not just the subject, but down to individual photographs it felt like a déjà vu.

It wasn’t to get hold of, until a couple of days later the Iranian photographer Solmaz Daryani came up and shared her concerns with a handful of colleagues about what she feels is a theft of her work. Daryani has been working on a personal project addressing Lake Urmia since 2014. And a number of images in Mann’s award-winning set are practically copies based on Daryani’s work. At first glance, it seems to be a clear case of plagiarism. But how is that to evaluate?

Lake Urmia

Situated between the provinces of East and West Azerbaijan in the Turkish speaking north-west Iran, Lake Urmia once used to be the sixth largest salt water lake in the world. Due to environmental mismanagement and infrastructural planning errors it has continuously been drying over the past years and by now has shrunk to a fraction of its former size. The freed salt blown by wind might desertify vast regions in Iran and the bordering countries of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Iraq.

The unfolding ecological disaster, the lake itself and its ecosystem have been subject to various documentary photography projects of various styles, mostly by regional Iranian photographers over the years. To name some: Abbas Kowsari, Azin Haghighi, Ebrahim Noroozi, Jalal Shams Azaran and Solmaz Daryani. Extensively photographed and documented, their long-term bodies of work, carried out over years, bear witness to a human made environmental tragedy.

Striking resemblance

Much has been said on the issue that photographers have occasionally due to different organisational, logistic or even security reasons photographed the same subject, often at the same time. This keeps happening daily with unfolding news events covered by different photographers for competing outlets and agencies in the age of imagery overflow.[1]

But apart from news and editorial feature photography, how is it with more personal photo projects on common topics? These sort of projects require extensive research and a variety of resources. While there have been claims here and there over the years, the difficult issue of plagiarism and appropriation has not been much addressed within this highly competitive industry. The outlined déjà vu with the extensively photographed topic of Lake Urmia might be a good case to discuss the issue in personal photography projects.

Maximilian Mann who describes his style as “poetic and calm” has been to Iran three times between September 2018 and February 2019 to conduct his final university piece “Fading Flamingos”. A well-executed project visually tackling an important environmental issue from a variety of angles — concise, aesthetic, solid documentary photography as it appears.

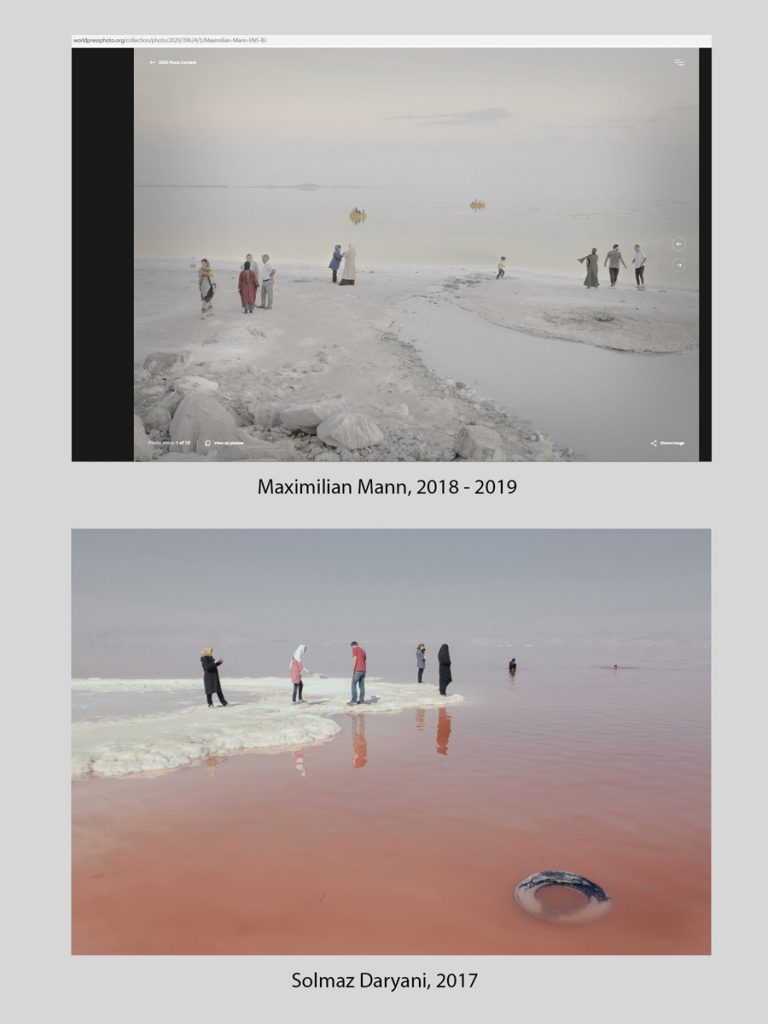

Tabriz-born photographer Solmaz Daryani’s long-term project “The Eye of the Earth” addresses Lake Urmia that she has been continuously working on since 2014. This project has been published on her website since 2016. A closer analysis of both projects lets a substantial number of Mann’s frames appear nearly as duplicates of Daryani’s. The locations, the frame angles, the lighting, even the hue of these pictures are surprisingly identical.

Already the opener of Mann’s set with a panorama depicting groups of people strolling in front of the Lake that melts together with the sky in the horizon has a pair in Daryani’s project. Still, that is a pretty standard photographic approach.

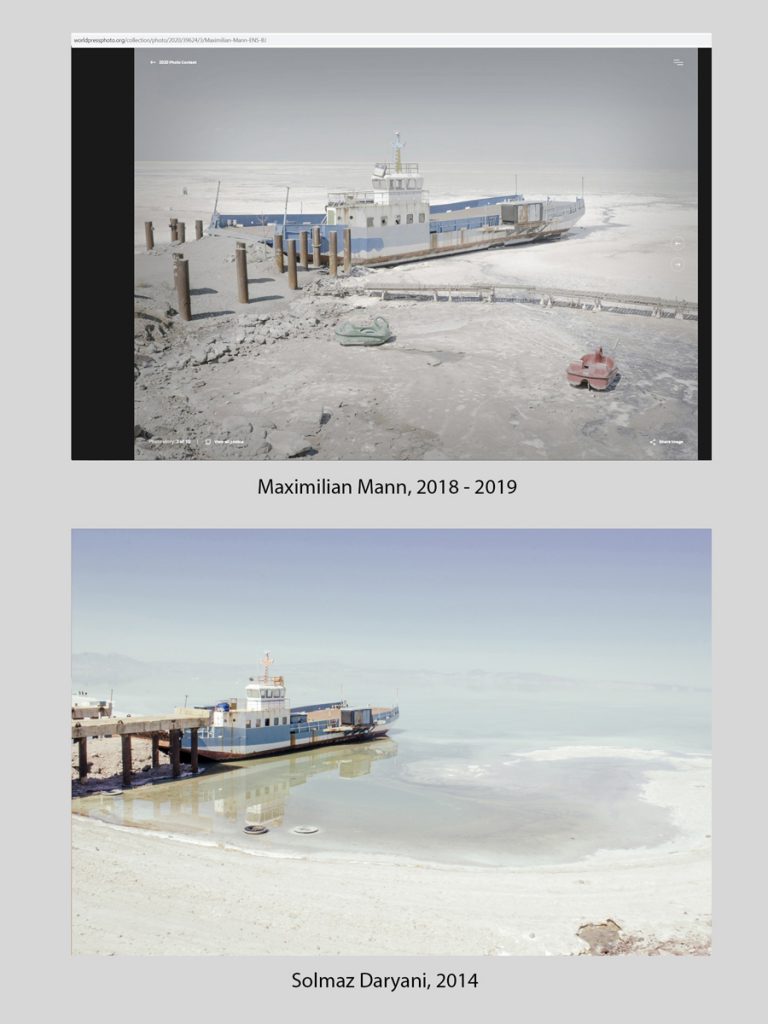

But already Mann’s second frame in the awarded set, a still life of the very same rusted ship wreck, notably taken from the same angle, from half a dozen wrecks laying in the area might justify raising eyebrows. Though to remain fair, one should state that the locations of both comparison figures above are among the most conveniently accessible places to take pictures of the Lake from.

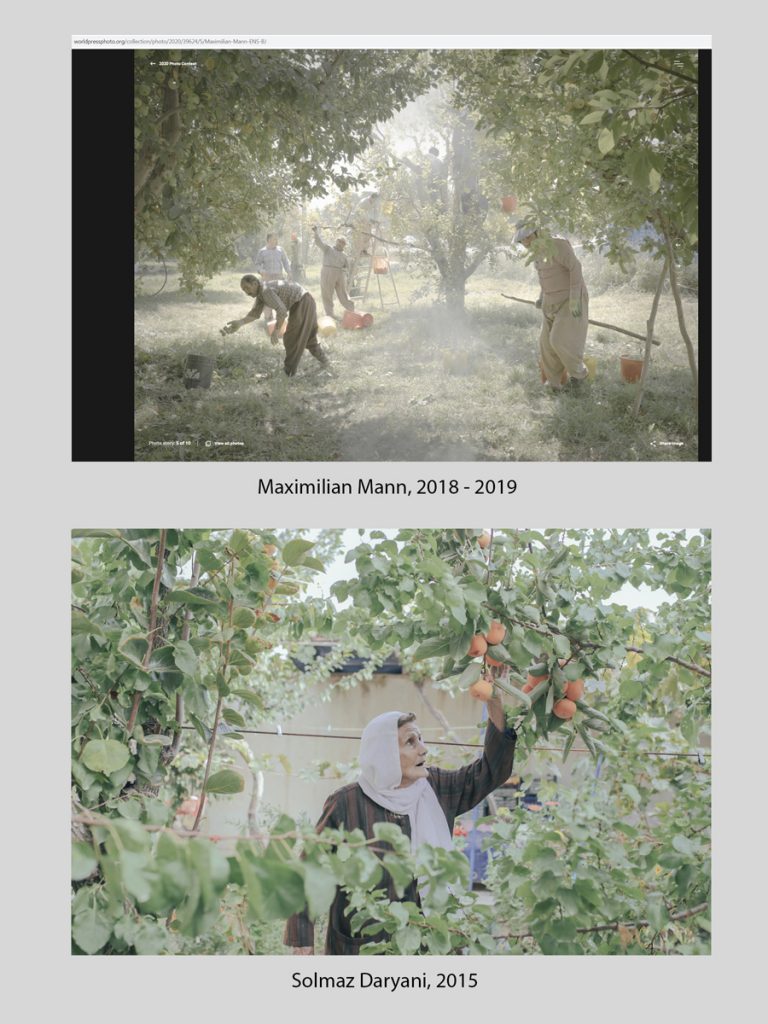

Yet the resemblances in content continue with harvesting apples and persimmons – common fruits in the lake region. But then such a matching desaturated green hue of the summer leaves goes along with the tender move of picking in both photographers’ pictures. The similarities in hue and posture keep appearing in pictures of men burning excess weed in the foreground of a hilly landscape in autumn.

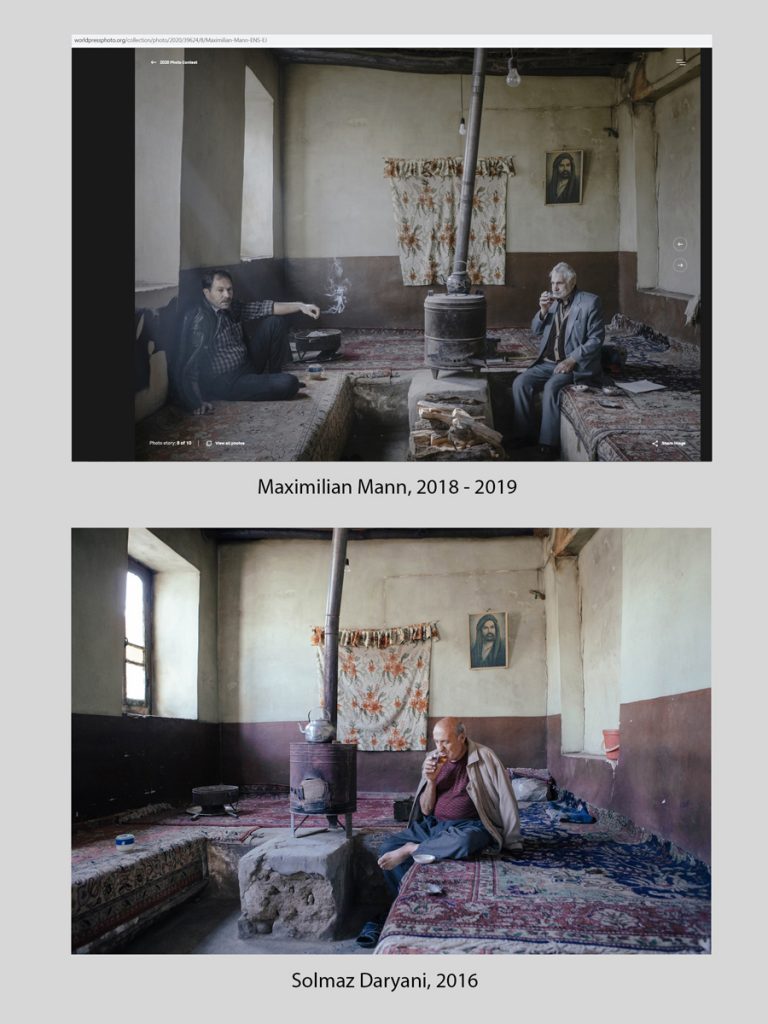

Then, again there is this strikingly similar choice of perspectives, exposure and hue, depicting the same sipping gesture of a man taken in the old tea room of Qalqachi, a rural place in the north of the Lake, so remote that even many locals to the area haven’t heard of.

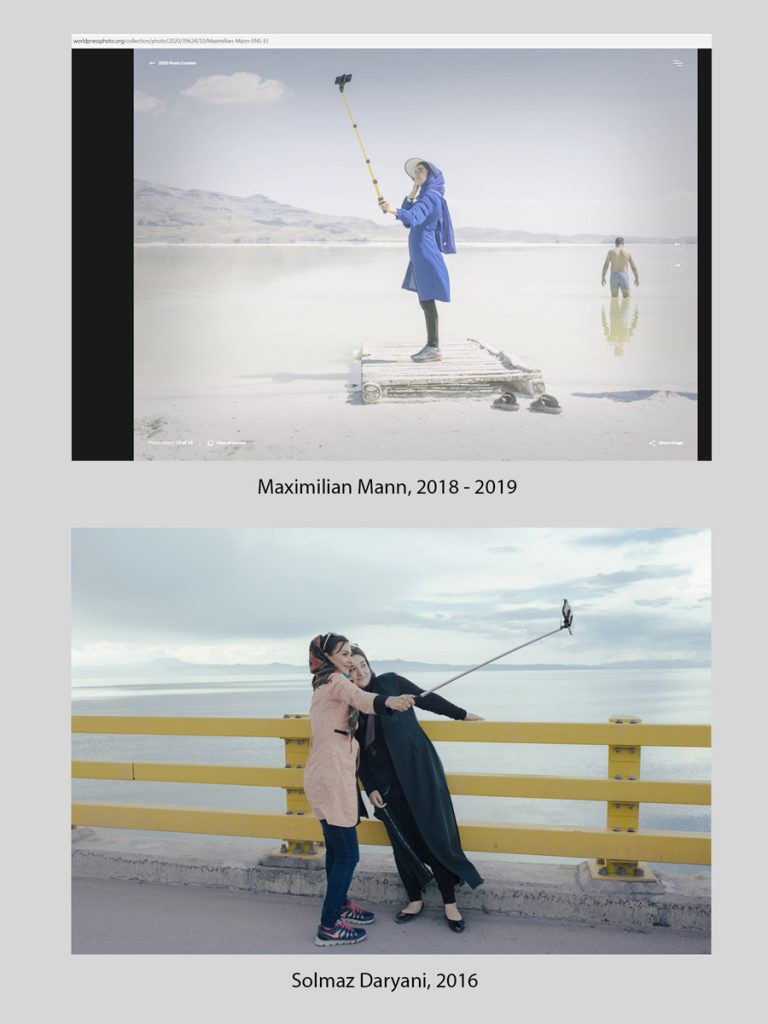

Not only is the content identical even down to specific elements such as the selfie stick, but also the formal structure and typology resembles in a picture of female tourists in colorful manteaux in front of the lake as they take selfies in the final frame of the awarded edit.

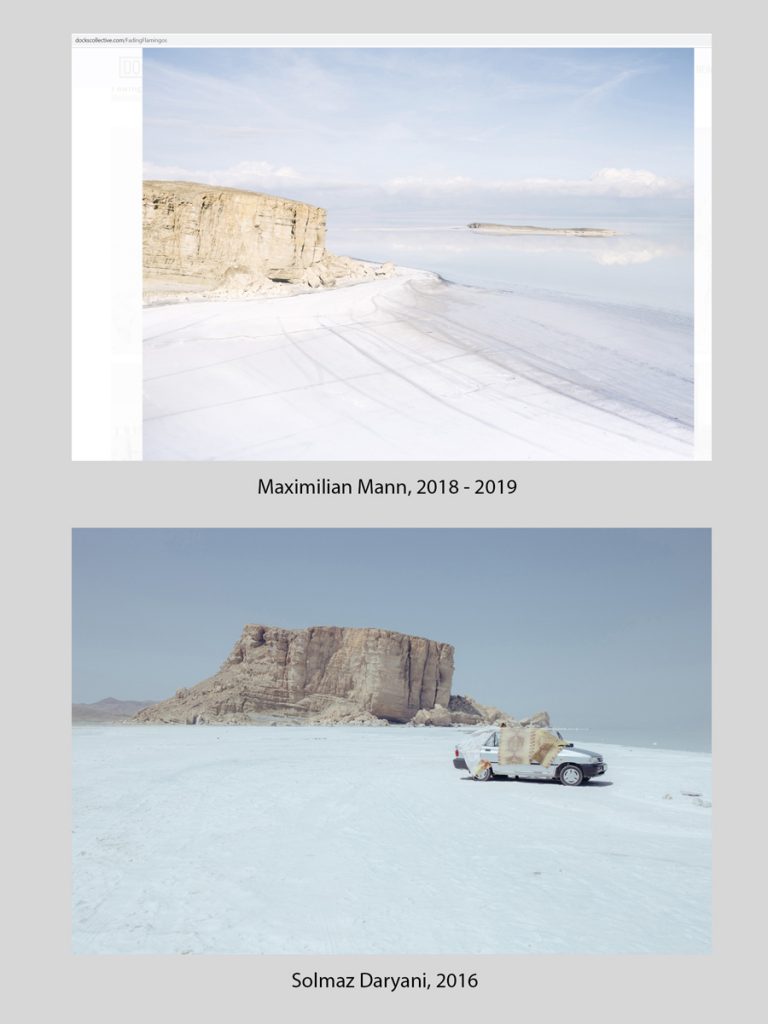

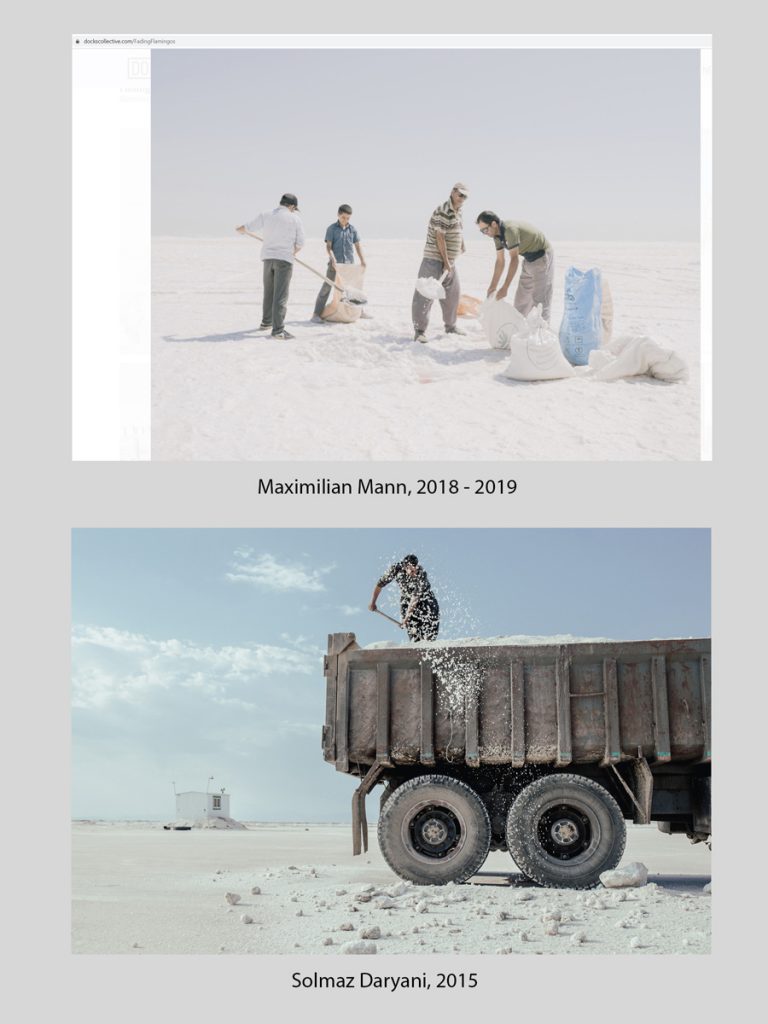

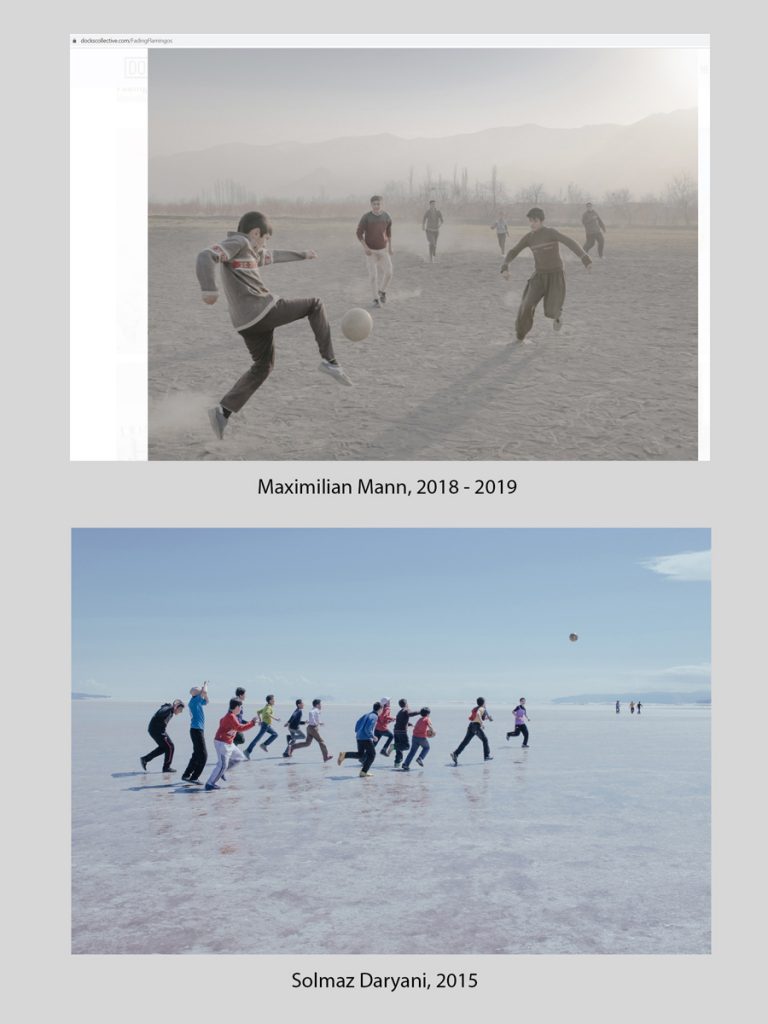

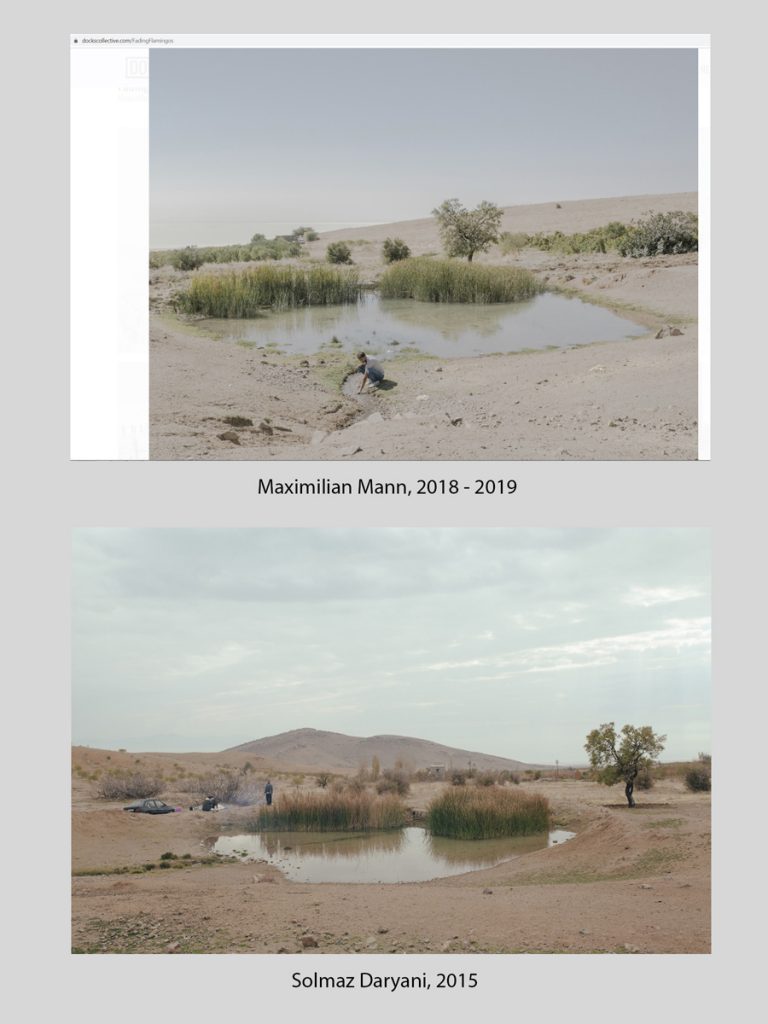

Apart from those identical pictures in the awarded set, a number of further pictures by Mann published on his collective’s website manifest commons with Daryani’s, too. Be it the depiction of the same side of a characteristic rock formation in Govarchin Qaleh, be it collecting salt with shovels from the dried bed of the lake for industrial purposes, or be it a picture of young boys in action as they play ball games in the lake area. And so forth, the chain of commons in content and locations, or in the depicted acts and typology of the subjects, formal structure and hue is seen in a total of at least ten frames.

The consistent similarities that are revealed by the direct comparison of the two projects, suggest that Maximilan Mann has had a persistent approach having the pictures of Solmaz Daryani in mind, or at hand as he has been visiting the sites she had photographed earlier. Ultimately this notion is underlined by the appearance of the very same pond in the middle of nowhere in both projects when tens of these ponds exist in the periphery of the lake.

Is it plagiarism?

The more cleverly and deliberately plagiarism is done, the harder to prove it is. Oxford’s Dictionary of Journalism defines it as “passing off another’s work as one’s own, which in journalism often means taking quotes, descriptions, and other material published in one media outlet and republishing them without attribution”.

Daryani, a self-taught photographer, is a native to the region who has grown up spending many holidays at the lake with her grandparents. Directly affected by the environmental shift, she has been conducting her personal in-depth photo-essay addressing the issue from 2014 on. Given the vast area around the lake and the remote situation of its some 200 surrounding villages, she has had to rely on her lived experience as a local for the project to come in shape. Over the past years her project has occasionally been published here[2] and there[3] raising attention about the environmental catastrophe and earning her some recognition.

As Mann states in his synopsis too, the original area of the Lake, i.e. the space in which most pictures have been taken is twice as big as the country of Luxembourg. Some of the villages and surrounding areas he has photographed are at times so remote that even locals might have difficulties getting there. Yet as the direct comparison of the questionable pictures from “Fading Flamingos” with those from Daryani’s “Eye of the Earth” suggests, he has managed to find himself in the very locations and match almost the same acts, perspectives, lighting, hue and seasons of at least ten frames which Daryani had photographed and published earlier in her personal project. Since the subject is not the Eiffel tower, ten identical pictures might be quite a few to be considered a mere coincidence. Thus the question occurs what the creative merit in Mann’s project is? Or speaking in terms of copyright, where does the threshold of originality[4] lay in such a case?

In a piece[5] written in partnership with World Press Photo, Mann’s verbatim leaves the impression as if there hasn’t been much of a discourse on Lake Urmia before his project: “When I first read about Lake Urmia I was very surprised; I had never heard anything about it before. A few weeks later I went to Iran for the first time and was shocked by the dimensions of the catastrophe”. At no instance does he reference nor acknowledge influence by Daryani’s work.

“It is very unethical and unfair to reproduce this many images of my story one by one.”

Solmaz Daryani

Daryani, feels that the core of her personal story has been stolen. She says: “There is nothing wrong to cover the same topic. In fact this helps for an important issue to become more visible. Still, it is very unethical and unfair to reproduce this many images of my story one by one. In my opinion Mann’s work is a disingenuous and poor imitation. Having said that, this might happen with a picture or two that depict the same thing in a project on a common topic, but here it looks very calculated”!

She continues: “As a female Iranian photographer, I have been facing so many obstacles and difficulties to carry on my work and to make it seen. Now a male photographer from Germany parachutes in and remakes a part of my project without any acknowledgement. Even worse, he manages to deprive it from its personal context. But the awards are supporting his approach.” She adds: “This hurts so much. ‘Eye of the Earth’ is a very personal story of my family and people around the lake, and I share so many personal bonds with it. Now it is hijacked.”

Conclusion

Despite the striking resemblances with Daryani’s project, “Fading Flamingos” has gained Mann a series of prestigious international and national industry accolades apart from the recent World Press Photo nomination. The project is also shortlisted for the Sony World Photography Award 2020, has received a Silver Medal at the College Photographer of the Year 2019, the 2nd place at the IAFOR Documentary Photography Award 2019, a Grant of the German Photographers’ association BFF in 2019, a nomination for the W. Eugene Smith Student Grant 2019 and selected for exhibition at the 7th Lumix Festival for Young Photojournalism to name a few.

Eventually much speaks for Mann’s project being a surgical and aestheticised remake aimed at the photo award industry. But the initial question if “Fading Flamingos” is a case of plagiarism, leads to a number of others that the photojournalism community and industry are urged to deal with. Where is the border of plagiarism in visual journalistic work and how is it to define? Are awarding politics in this competitive but budget-tight industry not endorsing such surgical approaches for success? What is the role of institutional actors such as the World Press Photo foundation in such cases? What recourse is there especially for marginalised photographers who clearly feel and suspect that their work has been stolen? Is there a way to speak up without being stigmatised? What is the common understanding in regards of appropriation of local and regional photographers’ work?

It’s certain that Oxford is not the authority here. Rather will it be on the professional community to discuss the issue and develop transparent ethical codes. Yet here too, a constructive discussion cannot evolve only on a technical side but detached from addressing the power structures involved in the industry and the imbalance of privileges induced by gender, race and class that could not be more evident in the particular case.

[1] https://time.com/3784386/two-takes-one-picture-two-photographers/

[2] https://www.emerge-mag.com/2018/06/the-eyes-of-earth-solmaz-daryani/

[3] https://www.polkamagazine.com/une-photographe-immortalise-la-disparition-dun-lac-en-iran-la-terre-de-son-enfance/

[4] Cp. Schöpfungshöhe

[5] https://wepresent.wetransfer.com/story/maximilian-mann-world-press-photo-2020/