The publication of my article “When Carbon Copies fade” on 10th March 2020 has led to a number of investigations regarding the questioned work by the photographer Maximilian Mann. As some of these investigations by institutional actors of the industry go into a decisive phase, Mann’s collective Docks has published an undated text titled “When plagiarism accusations fade”. It aggressively addresses my research and writing, and was brought to my attention by the evening of 6th April 2020.

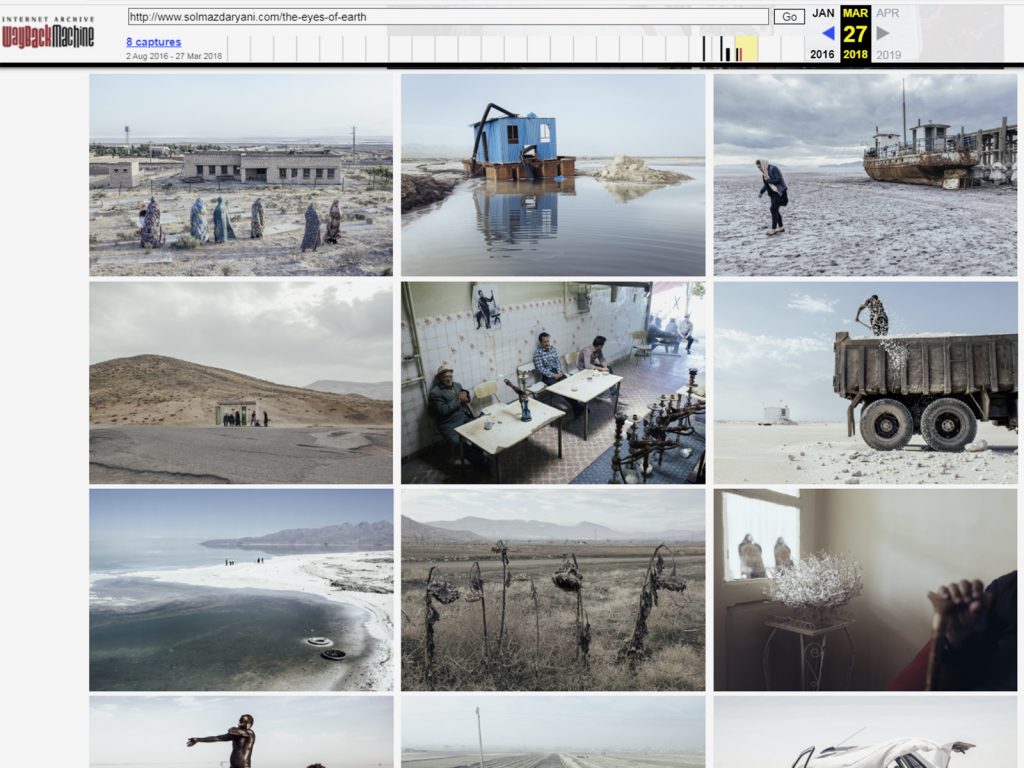

Docks collective’s undated text has a speculative nature and presents the unnamed author’s assumptions as facts upon which it aggressively concludes. It only provides a lead that at two different points in time, namely on 28th April 2019 and on 8th October 2019, Solmaz Daryani’s personal website did not contain a majority of the pictures in question. At the same time it omits the fact that on the same source, archive.org whose crawler randomly visits websites across the internet, is a gap of saving points for the pages containing Daryani’s corresponding project between 27th March 2018 and 28th April 2019. Interestingly that 13-month-long period very much overlaps with the time in which Mann has been producing his story.

Screen grab showing Wayback Machine’s saving point on 27th March 2018 from Solmaz Daryani’s project “The Eyes of Earth” on her website

From this meager lead, Docks collective concludes aggressively that the only explanation must be that Solmaz Daryani has willfully doctored her project after World Press Photo’s 2020 nominations were announced. The piece reads “Maximilian Mann’s work was completed in January 2019 and was also published several times before October 8, 2019. It was therefore impossible for Maximilian to know Daryani’s 9 pictures in question during the entire process of his work”. This conclusion is based only on a malicious assumption but not on any fact. Could Mann or someone at Docks collective please explain why a publication before 8th October 2019 shall serve as a proof for Mann not to have known Daryani’s pictures photographed between 2014 and 2017?

In his initial statement provided to me and to Peta Pixel by 11th March 2020, Mann writes “I acknowledge that in the selection I submitted to World Press Photo, there are similarities to the work of Solmaz Daryani that cannot be dismissed. However, Solmaz’ project also consists of many other photographs”. This is in stark contrast with the claim of his collective reading “Maximilian Mann could not have plagiarized images that he had never actually seen”. Why did Mann who has been keen to “strictly” reject plagiarism in his initial statement, admit there to have known her work and written of similarities in edit “that cannot be dismissed”? Is that not contradictory?

As far as my articles and activity are addressed by Docks collective, “When Carbon Copies fade” has raised structural issues within the photojournalism industry for which “Fading Flamingos” is a symptomatic example. There I have concluded “much speaks for Mann’s project being a surgical and aestheticised remake aimed at the photo award industry. But the initial question if “Fading Flamingos” is a case of plagiarism, leads to a number of others that the photojournalism community and industry are urged to deal with. Where is the border of plagiarism in visual journalistic work and how is it to define? Are awarding politics in this competitive but budget-tight industry not endorsing such surgical approaches for success? What is the role of institutional actors such as the World Press Photo foundation in such cases? What recourse is there especially for marginalised photographers who clearly feel and suspect that their work has been stolen? Is there a way to speak up without being stigmatised? What is the common understanding in regards of appropriation of local and regional photographers’ work?”

That nuanced conclusion has raised whole structural issues to the photojournalism and documentary photography community. Despite that, interestingly both in Mann’s initial statement, and in the newer, undated piece published by his collective, the authors feel the urgency to discharge Mann from plagiarism, and to continuously detract from the questions raised regarding the appropriation of local photographers’ work.

Nowadays we can find pictures of the same locations from different photographers by searching for them in online picture databases or even by hash- and location tags on social media. What makes a body of work in documentary photography distinct, is the narrative that it constructs through the combination and interaction of a number of frames and photographic style.

The similarity of narration in Mann’s work on Lake Urmia to Solmaz Daryani’s – and as he points out himself also to that of a number of other Iranian photographers – is a key issue for doubts on his project’s threshold of originality. I have discussed this thoroughly in my rebuttal of Mann’s initial statement. He and his collective have so far completely ignored to address this issue, yet have at the same time launched continuous efforts to detract from it, too. Whatever outcome the institutional investigations in this matter will have, this and the structural questions raised through my articles will notwithstanding remain.

Regarding my source work, I have received and verified Solmaz Daryani’s picture comparisons that raise questions by February 29th, 2020. By then they had been published on her website. She had even provided me one more image comparison. I chose not to publish that one, as she had disclosed to me “this one has never been published, thus it would be unfair to use it in order to raise the issue”.

Eventually, given the explanations above, the aggressive, wrongly-concluded, yet authoritative and self-righteous tone in Docks collective’s piece wakes in me the notion of victim blaming efforts aimed at Solmaz Daryani. One may hope that Mann’s working ethics contrast with his collective’s argumentation and conclusion style.